April 27, 1934 - December 29, 2020

New York Times obituary by Katherine Q. Seelye

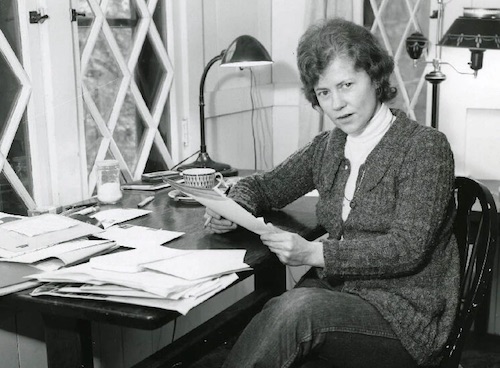

Jean Valentine, Minimalist Poet With Maximum Punch, Dies at 86

Jean Valentine, a former New York State Poet whose minimalist, dreamlike poetry was distinguished by crystalline imagery followed by an unexpected stab of emotion, died on Dec. 29 in Manhattan. Her daughter Rebecca Chace said the cause of her death, in a hospital, was complications of Alzheimer’s disease.

Over a six-decade career, Ms. Valentine published 14 collections of poetry. Seamus Heaney once described her verses as “rapturous, risky, shy of words but desperately true to them.”

She received the 2004 National Book Award in poetry for “Door in the Mountain: New and Collected Poems, 1965-2003” and was a finalist for the 2011 Pulitzer Prize for “Break the Glass,” a collection of poems, the Pulitzer citation said, “in which small details can accrue great power and a reader is never sure where any poem might lead.”

Indeed, her readers can feel sure-footed, only to find themselves suddenly startled. As she wrote in “A leaf, a shadow-hand,” in its entirety:

A leaf, a shadow-hand

blows over my head

from outside time

now & then

this time of year, September

—this happens—

—it’s well known—

a soul locked away inside

not knowing anyone,

walking around, but inside:

I was like this once,

and you, whose shadow-hand

(kindness) just now blew over my head, again,

you said, “Don’t ever think you’re a monster.”

Many of her poems first appeared in The New Yorker. In an interview, Alice Quinn, the magazine’s former poetry editor, described Ms. Valentine’s voice as “intimate and urgent, uttering something precise and necessary to say just then.”

Ms. Valentine was not overtly political, but she occasionally touched on public events. In “September 1963” — a seismic date in civil rights history, when members of the Ku Klux Klan bombed the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., killing four Black girls — she writes of her innocent trepidation in dropping off her child on the first day of school and her relief at seeing the children play together.

Glad, derelict, I find a park bench, read

Birmingham. Birmingham. Birmingham.

White tears on the white ground.

White world going on, white hand in hand,

World without end.

“That poem is devastating,” the poet Anne Marie Macari, Ms. Valentine’s literary executor, said in an interview. “Instead of the poem being an idea, you enter the experience. You feel the grief in your body. You feel the grief of history in just those few lines.”

Ms. Valentine favored clear, taut images, so concise they could seem like fragments. It was the immediacy of emotion she was after, and she often found it in dreamscapes.

“I had a teacher in college who said, ‘You could write from your dreams,’” she told Ploughshares, the literary magazine, in 2008, “and that was like being given a bag full of gold.”

Asked once by the poet John Hoppenthaler how she achieved that dream state in her writing, Ms. Valentine responded, “Well, I actually go to sleep and dream.”

In “The Windows,” she writes of what she calls a “funeral dream,” in which she declares: “You may be dead but/Don’t stop loving me.”

“She was brilliant at evoking the power of love and the endlessness, the indwelling aspect of eternity that we feel,” Ms. Quinn said. “She reproduces the drama of recalled words and moments, which manage to convey the ineffable.”

Ms. Valentine learned her craft in the late 1950s and ’60s, when the poets Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton were pushing the boundaries of first-person revelation with what came to be called confessional poetry.

Ms. Valentine, who studied informally with Mr. Lowell, was more restrained and oblique. As she wrote in the last few lines of “Sanctuary”:

What happens when you die?

What do you dread, in this room, now?

Not listening. Now. Not watching. Safe inside my own skin.

To die, not having listened. Not having asked …

To have scattered life.

Yes, I know: the thread you have to keep finding, over again, to

follow it back to life; I know. Impossible, sometimes.

Jean Purcell Valentine was born on April 27, 1934, in Chicago. Her mother, Jean (Purcell) Valentine, was a homemaker, and her father, John Valentine, worked in finance. She was raised in Orinda, Calif., near where her father was stationed in the Navy, and in Boston.

She graduated from Milton Academy in Massachusetts in 1952 and went to Radcliffe, where she majored in general studies and developed her interest in poetry under the mentorship of William Alfred, the playwright, poet and longtime Harvard professor.

While there, she met James Chace, a Harvard student. They married in 1957, a year after she graduated, and moved to New York. He went on to become a historian and an expert in American foreign policy, in addition to serving a stint as an editor at The New York Times Book Review.

At 30, a married mother of two, Ms. Valentine had never been published and was about to give up on poetry when she won the Yale Series of Younger Poets Award in 1964.

The untitled manuscript that she had submitted as her application was published a few months later as “Dream Barker and Other Poems” (1965).

That led to her invitation to give a reading at Harvard in 1965. When Mr. Alfred introduced her at the reading, he said that she was not a show-off writer trying “to make a parade of clever sensibility.”

Rather, he said, her poems “are charged with hard-bought impressions of life.”

“There is no slackness in them,” he added. “The flow of sound and the flow of feelings are one.”

She and Mr. Chace divorced in 1966. The next year, she returned to Radcliffe on a Bunting Fellowship, her two young daughters in tow, and studied with Mr. Lowell, though she was not officially his student. He held informal workshops, called “office hours,” for budding poets, and she thrilled to hear him read her work in what she called his “eccentric” voice.

She and Mr. Chace remarried each other in 1968 and divorced again in 1969. In 1991 she married Barrie Cooke, a British-born Irish painter whom she had also met in college, and with whom she lived in Ireland. They divorced in 1996.

In addition to her daughter Rebecca, she is survived by another daughter, Sarah Valentine Chace; a sister, Ann Cobb; a brother, John Valentine; two granddaughters; and her longtime companion, Monty Arnold.

Over the years, Ms. Valentine taught widely and led poetry workshops, at, among other places, Barnard, Yale, Hunter College, Sarah Lawrence, Columbia, and the 92d Street Y.

She served as the New York State Poet from 2008 to 2010, promoting poetry through readings and talks. She did much of her writing at artist colonies; she was a fellow at MacDowell, in Peterborough, N.H., 14 times.

In addition to writing poetry, she collaborated with the Russian poet Ilya Kaminsky to interpret into English the work of Marina Tsvetaeva, the tragic Russian poet whose work was famously untranslatable.

Ms. Valentine was in her 80s when she was awarded Yale’s prestigious Bollingen Prize for American Poetry.

“Jean Valentine is fearless when moving into charged territory,” the prize’s judging committee wrote. “Without compromising substance or sacrificing a reckoning with painful reality, inequity and loss, there is solace and spirituality, and she radiates responsibility as a voice of clarity and compassion.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

home poems shirt in heaven bio collected photos